Winner of the international data journalism competition The Sigma Awards 2021.

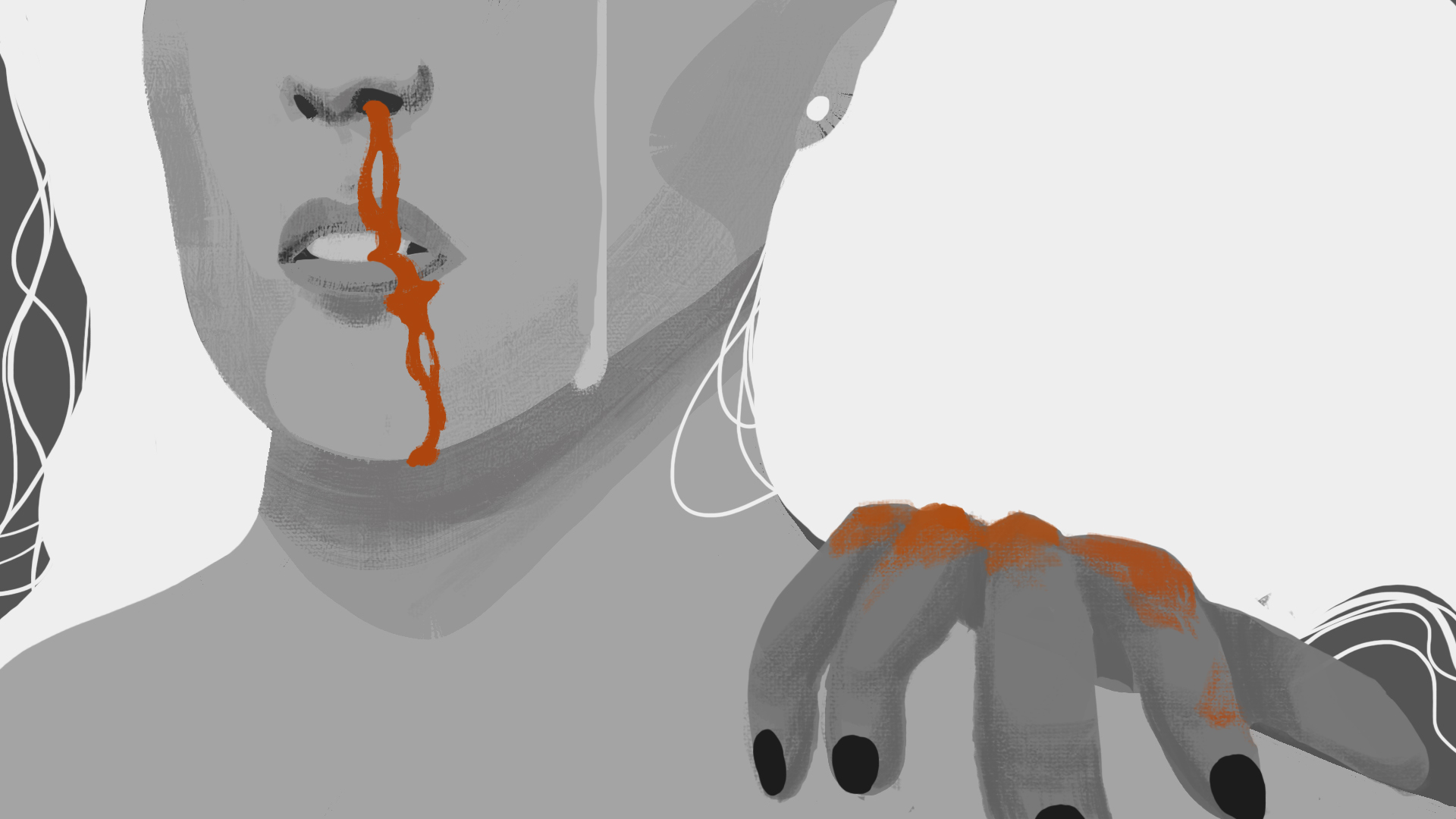

Content warning: This article contains graphic descriptions of violence against women.

In early 2020, several shocking cases of domestic violence in Kyrgyzstan came to light, including some that resulted in the women’s deaths.

One such tragic case occurred in the Kochkor district of the Naryn Region, where 36-year-old Ayday died after a beating (editor’s note: the names of all subjects in this article have been changed). On New Year’s Eve, the police arrived at the crime scene after a call from paramedics and found multiple markings and bruises on Ayday’s body.

The suspect was found almost immediately: Ayday’s husband, Bakyt. He cited financial issues in the family as the reason for the severe beating that led to her death. He told the police that he hit his wife several times in the face, and after she fell, he kicked her in the head until she lost consciousness.

Human rights activists from the Association of Crisis Centers attended Ayday’s court case and stated that the man realized his wife had died at 9pm. However, only after midnight did a paramedic arrive at the home and pronounce her dead. The defendant was not able to explain to the lawyers representing Ayday what he did in the intervening three hours.

Human rights activist Tolkun Tyulekova recalled the circumstances of Ayday’s murder. “On the evening of the murder, there was another relative in the house, but they did nothing. Apparently, the neighbors heard screaming and called the police. In the intervening period, he [the husband] changed her clothes and washed her. Ayday’s father said that when they went to the morgue to identify the body, he tried to stroke her head and tufts of hair fell into his hands. The husband reportedly dragged Ayday by the hair, causing her hair to fall out in clumps. This shows how severely he beat her while sober.”

Bakyt was sentenced to 10 years in prison and ordered to pay a fine of 110,000 soms. Ayday’s family, who now support Ayday’s four children, received only 30,000 soms in personal damages. Dozens of women are murdered in Kyrgyzstan every year, often at the hands of a spouse, boyfriend, ex-husband, or male acquaintance. In international policy terminology, this is called femicide.

*Femicide is the murder of a woman, usually committed by a man on the basis of misogyny, gender discrimination, and/or as a result of gender-based violence in which the state is complicit.

Femicide arises as a result of the idea of men’s superiority over women — for example, when a man believes he has the right to ownership of a woman. Femicide often occurs when a man forces a woman to conform to stereotypical gender roles. Other causes of femicide in Kyrgyzstan include jealousy, cultural expectations (i.e., “a woman should or should not do x, y, z”), bride kidnapping, a woman refusing an intimate relationship or marriage, a woman attempting to leave an intimate relationship, and other related reasons.

Kloop’s journalists analyzed homicide statistics and more than 54,000 news articles in order to better understand the prevalence of femicide in Kyrgyzstan. Our analysis reveals that women in Kyrgyzstan are most often killed by their husbands or intimate partners and that femicide is a direct consequence of domestic violence.

Home is one of the most dangerous places for women in Kyrgyzstan

A 2019 United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC) global homicide study suggests that the contexts in which men and women are killed are fundamentally different. Men are killed largely outside the home during thefts, robberies and other crimes, as well as armed conflict. Women are killed at home by their husbands, lovers, and partners. Nearly 60 percent of murdered women worldwide are killed by their intimate partners.

According to the UNODC report, “Home is one of the most dangerous places for women, who continue to be victimized as a result of inequality and gender stereotypes.” Our analysis shows the same situation in Kyrgyzstan.

In the last ten years, statistics from the Prosecutor General’s Office showed that there were 762 murder cases where a woman was killed. In 80% of cases, men committed the murder. During the same time period, women committed only 10% of murders, usually in self-defense against an abusive partner.

From studying the details of murder cases, we identified more than 300 cases of femicide in Kyrgyzstan since 2008. There are likely many more cases of femicide, but we were unable to locate the details of every murder case. Our analysis shows that in 75% of cases, femicide was committed by a person who knew the female victim, usually an intimate partner, relative, or friend. In most of the cases identified, husbands murdered their wives. Only in 11% of cases was the perpetrator a complete stranger to the victim.

“She wouldn’t let me watch TV” and “she was slow making lunch”

At the end of September 2019, 51-year-old Adyl struck his wife with an axe while she slept. A criminal case alleging murder with particular cruelty was brought before Sokuluk District Court.

During the hearing, it was revealed that Adyl had bought the axe for 400 som two months before the murder and had concealed it in the shed.

It was likewise revealed that Adyl had killed his wife because “she was always bothering him, turning off the television while he watched.”

On the day of the murder, Aizady had a headache and turned off the television. Adyl was furious. He waited until his wife was asleep, then retrieved the axe from the shed and struck Aizady in the head several times.

“I don’t regret the crime at all. I had planned to kill her for a long time and would have killed her regardless,” he declared during the hearing.

The court found him guilty and sentenced him to 14 years in prison.

According to our data, the majority of femicide cases are committed with knives or bare hands. Other common murder weapons include axes, shovels, and rocks. The murders are aggressive, committed with particular brutality. There are very few cases limited to a single point of trauma.

In two out of three cases of femicide, the victim’s body is marked by numerous injuries and multiple knife wounds.

In most cases, femicide takes place in the context of family disputes. The violence can be prompted by almost anything, from a simple question to a woman’s attempt to flee from her aggressor. Men justify their actions as natural anger, or as an inability to hold back after the woman, as they see it, has done something wrong.

The government “really tries,” but it is difficult

Our analysis shows that femicide in Kyrgyzstan is often preceded by domestic violence. Many murdered women are first subjected to systematic beatings by their husbands and partners.

However, the MVD does not want to directly link femicide with domestic violence. Although official inquiries have gone unanswered, they have said as much in unofficial conversations with reporters.

The MVD keeps statistics on murders linked to domestic violence. However, they do not reflect reality. From 2017-2018, according to MVD data, eight criminal cases were filed charging murder as a result of domestic violence. In the same period, we were able to identify significantly more: 25.

The MVD calls the problems of domestic violence and violence against women “extremely important,” but admits that work in this area is “difficult.” They are “concerned that not all victims file official complaints.”

Shabdan Kayipov, representing the Social Development Ministry, acknowledges that preventative and early-warning measures against domestic violence are “not enough” and blames this on insufficient personnel and the difficulty of identifying such cases.

“Identifying domestic violence is a big problem for our team, because most women who have experienced domestic violence hide it. They don’t want to ruin their relationship with their husband,” he said.

The director of the Crisis Center Association, Tolkun Tyulekova, emphasized that women rarely turn to the police, and are afraid to leave their husbands for many reasons, including the threat of violence towards themselves and their children, pressure from relatives, distrust in the police, and a lack of money or alternative housing.

“A lot of women are pursued by their husbands after they decide to leave them because of systematic abuse. This pursuit can also lead to murder, but the police don’t respond to it at all,” she said.

Tyulekova cited one case that occurred in the village of At-Bashi during quarantine. A woman divorced her husband and went to live with relatives. The husband arrived and shot her, but missed. The woman tried to run away, but the man caught her and struck her head with a rock. She was taken to the hospital, and the man ran off. The police caught him and he was charged with attempted murder.

Deferred femicide

Considering the volume of domestic violence cases in Kyrgyzstan (around 7000 cases per year in the last few years) and the difficulty of punishing the aggressor, it is clear that a victimized woman can be killed at any moment. Furthermore, women experiencing domestic violence may die not only on the day the trauma is inflicted, but also some time later. In that case, the deaths are not recorded in domestic violence statistics. This is known as ‘deferred femicide’.

“It’s important how the violence is categorized. If he killed and hung her, that could be mistakenly classified as a suicide. A woman might be raped and left with injuries she later dies from, but that isn’t written down as a murder. They say she died from ‘external causes’. The damage done to a victim’s health in the long term can cause her to die,” says Tolkun Tyulekova.

In June 2020, a woman appealed to the Crisis Center Association for help. She had previously divorced her husband, who systematically beat her. In the past year, she had become ill, experiencing headaches that kept her from sleeping. When she suddenly took a turn for the worse, she was hospitalized.

“The woman told me that her husband constantly beat her about the head. The doctor explained that, because of the trauma, she needed surgery. But even with the surgery, she died two months later,” sayd Tolkun Tyulekova.

Violent deaths are not always prosecuted as homicides. The criminal code also contains offenses such as “negligent manslaughter,” “assault causing grievous bodily harm” (if it leads to death), and “incitement of suicide.”

While statistics on the last two counts have seen no notable deviation in the last ten years, questions have been raised by crimes prosecuted under the statute “Negligent manslaughter.”

In the last two years, criminal cases in which the victim is a woman have started to be registered under this article. In 2019, 11 women were recorded in this category. In the first ten months of 2020, 28 women were recorded in this category. Additional study is necessary to determine whether this number conceals cases of femicide.

As a practical matter, the government’s failure to acknowledge femicide as a distinct problem means its true scale is impossible to determine.

Analysis of the law shows that femicide in Kyrgyzstan is not considered a gendered crime and is not placed in a separate category. In 2019, criminal reforms reduced prison terms for murder. For a murderer to receive life imprisonment, the victim’s side (for example, the murdered woman’s parents) must show that the murder was commited with particular cruelty.

The data on femicide in Kyrgyzstan show that victims not only suffer from systematic beatings in life, but are killed with particular cruelty and numerous blows.

Despite this, the perpetrators are often given punishment in line with that of an ordinary murder. There exists at least one case where a husband escaped punishment entirely for the murder of his wife, since his crime was incited by his wife’s “severe verbal abuse, as well as prolonged mental trauma resulting from her amoral behavior.”

More details on our methodology and results can be found at this link. Data on femicide in Kyrgyzstan can be downloaded here.

This investigation was prepared as part of the Soros-Kyrgyzstan’s Foundation’s Media Development Project.

Authors: Anna Kapushenko, Savia Khasanova

Illustrations: Anna Pechenkina

News Scraping: Edil Bayizbekov

Editor: Aziza Raimberdieva

Translated by Hallie Sala and Sameera Ibrahim from Respond Crisis Translation