Kyrgyz authorities allege Bolot Temirov is a drug user and used falsified identification documents. But case files obtained by reporters suggest a high-level effort led by the GKNB security agency to silence him.

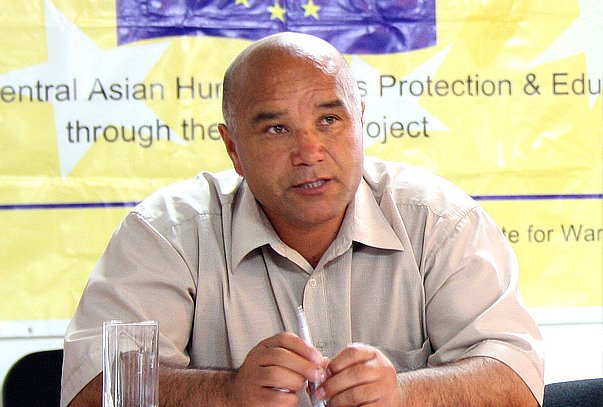

To his tens of thousands of viewers, Bolot Temirov is a crusading investigative journalist waging an uphill battle against corruption in his native Kyrgyzstan. He and his investigative video outlet Temirov LIVE have devoted themselves to exposing corruption in this small Central Asian country.

But to the Kyrgyz authorities, he’s a foreigner engaged in provocations against the country’s government. And that isn’t just invective; they accuse him of submitting fraudulent documents to obtain his domestic and foreign passports and then of using them for international travel.

“I consider all these criminal cases to be dreamed up out of thin air,” Temirov told OCCRP and Kloop.

But the penalty he faces — up to as much as 20 years in prison — is severe, and the outcome of his trial is becoming a widely-watched indicator of Kyrgyzstan’s commitment to press freedom.

His prosecution began earlier this year when, as Temirov says, he angered the head of Kyrgyzstan’s powerful GKNB security agency by investigating his family’s business dealings.

The GKNB head, Kamchybek Tashiev, denies that the journalist’s investigations into his family’s business have anything to do with the case, and has insisted that his agency was barely involved.

But in a new investigation, journalists from OCCRP and its Kyrgyz partner, Kloop, have analyzed documents from the case against Temirov and found multiple red flags. The findings strongly suggest that his prosecution represents the deliberate targeting of an outspoken journalist, and not — as the official narrative would have it — the routine pursuit of a criminal matter.

According to the police, the most serious allegations against Temirov were uncovered during an initial investigation into a hashish possession charge. In fact, however, the documents show that the GKNB had requested information about Temirov’s domestic passport and monitored his travels months earlier. The absence of a formal criminal case against Temirov at the time raises questions about why the authorities were looking into him.

Even the original justification for a January raid on the Temirov LIVE office, when a small bag of hashish was found on Temirov, shows signs of being falsified or manipulated.

The situation fits a pattern observed in two other recent cases. After making influential enemies in Kyrgyz politics, a rights activist and a popular blogger were both charged with shocking crimes that would do damage to their reputations. Both also faced additional charges, including for allegedly falsifying documents.

Leila Nazgul Seiitbek, a Kyrgyz lawyer and rights activist who received asylum in Austria after facing politically motivated charges, said that Kyrgyz authorities typically open an initial charge to take aim at a person’s reputation or as an excuse to begin a fishing expedition.

“Once they have the decree on initiating the criminal case, they have wider authority and can request all kinds of things,” she told OCCRP.

Tashiev and President Sadyr Japarov came to power in late 2020 in the wake of a popular uprising against the results of a controversial parliamentary election. Rights groups and political scientists have pointed to multiple violations of democratic procedures during that tumultuous time. They have also warned of a subsequent deterioration in Kyrgyz democracy, including the adoption of a new constitution that places more power in the president’s hands, legislation to limit freedom of speech, and a rise in illiberal populist activism.

Against this backdrop, Temirov’s prosecution will be a bellwether, rights groups say.

“The court case that is now underway against Temirov is a test of Kyrgyzstan’s commitment to rule of law, to due process, and to media freedom,” said Gulnoza Said, a program coordinator for the Committee to Protect Journalists.

The Kyrgyz authorities, including Tashiev, did not respond to questions by OCCRP and Kloop but in other media denied any impropriety.

A History of Harassment

The criminal cases pursued against Temirov this year are not the first time he and his team have faced pressure from the authorities.

In October 2021, Temirov LIVE staffers began to notice suspicious cars parked outside their building. A few months later, Temirov’s family discovered a hidden camera recording the living room of their rented apartment from behind the wallpaper. According to Temirov, footage from that camera was used in propaganda videos against him later published online.

Most shockingly, sources said a young male who pursued a romantic relationship with one of Temirov LIVE’s female employees was a GKNB agent. Surreptitiously recorded footage of a sexual encounter between them was then used to blackmail her. That video, too, was published online.

But while the previous harassment of Temirov LIVE seemed focused on surveilling or scaring the journalists, this year began with a serious escalation.

On the evening of January 22, Kyrgyz law enforcement raided the Temirov LIVE office. After forcing Temirov and his colleagues to lie face down on the floor, they raised him off the ground, unbound his hands, and instructed him to empty his pockets. Out came a small cellophane packet of something green, later determined to be hashish.

“They planted it!” Temirov shouted as the police dragged him out.

The authorities then added three more charges. They accused Temirov, who, like many in Kyrgyzstan, is also a citizen of Russia, of falsifying documents to receive his domestic and international Kyrgyz passports. Based on that claim, they also charged him with illegal border crossing when he traveled abroad.

A month later, an interior ministry investigator annulled Temirov’s passports.

The Passport Case

While Bolot Temirov clearly has a right to Kyrgyz citizenship, he also has Russian citizenship. Prosecutors are now alleging that he used someone’s documents to obtain his Kyrgyz passport.

Temirov was born in 1979 in Soviet Kyrgyzstan and says he is a Kyrgyz citizen by birthright.

In 2001, while in graduate school in Moscow, Temirov received Russian citizenship. While Kyrgyzstan places some restrictions on dual citizenship, having a second passport is legal.

In 2006, Temirov returned to Kyrgyzstan and took a job at a state-run TV channel. Two years later he received a Kyrgyz passport.

Prosecutors now allege this procedure was illegal. They claim that, in order to receive his passports, Temirov submitted documents actually belonging to other people: a “military ticket,” which certifies that an individual served in the Kyrgyz armed forces, and a temporary ID, which is typically issued before issuing a passport.

Temirov denies falsifying any documents.

Questions About the Case

But for all the force of the Kyrgyz authorities’ accusations, there are some serious issues with the case dating back to the official start of the investigation.

The January 22 raid on the Temirov LIVE office took place after a young woman named Aiperi Adyl kyzy filed a police complaint against Bolot Nazarov, a Kyrgyz poet who had worked with Temirov’s team and performed their investigations as folk songs. She claimed that Nazarov had forced her to take drugs, including in the Temirov LIVE office. She also claimed that Nazarov told her he received the narcotics from his boss, who was also named “Bolot,” and gave a partially accurate description of the office itself.

That afternoon, the police questioned her and registered the information in an official document, writing that the alleged perpetrator was Bolot Nazarov.

And then something unusual happened. When police opened a criminal case, they referred to the perpetrator as an “unknown person by the name of ‘Bolot’.”

“When investigators have every opportunity to identify the perpetrator, they are obliged to do so, in theory,” lawyer and rights activist Seiitbek told OCCRP and Kloop. But, in practice, it doesn’t always happen if law enforcement has an interest in concealing his or her identity, she added.

Roughly an hour-and-a-half later, the police interviewed Adyl kyzy again, this time officially as a victim of a crime. Though she presented some details differently, she never wavered in her claim that it was Nazarov who had pressured her to smoke marijuana.

Once the questioning concluded, the police issued a document handing the case over to a group of investigators. But once again, they described the alleged perpetrator as an “unknown” Bolot.

This is what may have given them grounds to target Temirov at his office that evening.

According to the police, the subsequent passport charges against Temirov grew from the drug case. Additionally, GKNB head Tashiev has claimed that his agency was playing no significant role.

But case documents definitively demonstrate that the investigation began long before January — and that the GKNB was involved from the beginning.

They show that the GKNB requested information on Temirov’s domestic passport two months before Adyl kyzy ever went to the police. The case file includes a November 23 letter sent by the Ministry of Digital Development to the GKNB responding to a request the agency had sent for information on Temirov’s domestic passport.

While the document’s contents are not particularly revelatory, its existence demonstrates that the GKNB was already taking aim at Temirov’s citizenship even before the raid and the criminal case.

With no active investigation against Temirov at that time, there was no legal rationale for Kyrgyz law enforcement — let alone the GKNB, an agency officially focused on protecting national security — to investigate the journalist’s passport.

According to Ermek Baibosunov, a Bishkek-based lawyer, Kyrgyz law enforcement officers need a solid reason to surveil a person.

Flight records included in the documents also show that the GKNB was surveilling Temirov long before the drug case. One document registered him flying to Istanbul on May 27, 2021, and noted that, after Temirov passed through passport control, the border agents notified the agency’s Fifth Department, which according to the media is responsible for monitoring the media. (This was a month after Temirov LIVE published their first videos about Tashiev.)

Finally, the documents show that the GKNB viewed Temirov’s journalism as an inherent threat to the state. In a review of the Temirov LIVE YouTube channel, they found that the videos were “aimed at discrediting the country’s top military-political leadership, which could increase the potential for protest and negatively affect the socio-political situation.”

Agent Batur?

Other facts not covered in the case documents also suggest GKNB involvement.

After Temirov’s arrest in January, he and his team turned their investigative lens on the raid of their office. By examining police footage, security camera footage, and recordings made by journalists as police searched their office, they were able to reconstruct the raid and identify several questionable actions by law enforcement.

Most importantly, they found that two men — one of whom appeared to be neither a drug police officer nor a member of the Interior Ministry special forces — were coordinating the raid. The men appeared to be receiving and making multiple calls on their mobile phones throughout the evening, as if they were receiving instructions and reporting back to someone.

Initially, as officers approached the door of Temirov LIVE’s office, one of the two men instructed the police cameraman to wait before entering.

By the time he entered, the first wave of officers had already forced the journalists onto the ground and spent around a minute inside, potentially allowing someone to plant the drugs on Temirov without being caught on camera. (They also confiscated the computers where the Temirov LIVE team says they stored their own security camera footage, removing another independent source of accountability.)

In a later review, a Bellingcat journalist who helped Temirov LIVE with their investigation honed in on footage taken of a police officer’s cell phone screen. The phone listed the caller as “Batur SNB S5.”

“SNB” is an old abbreviation for the GKNB, while S5 appears to refer to its fifth department.

After Temirov LIVE received their confiscated equipment back from law enforcement at the start of July, they also discovered that on January 24, two days after the raid, someone had gone through their computers. But investigators were only given a court order to examine the computers on January 28, making their actions illegal, the journalists allege. The team notes that propaganda videos featuring files from their computers appeared online during that period.

Traditional Tactics

The GKNB is the most powerful security structure in Kyrgyzstan and traces its lineage back to the infamous Soviet KGB.

According to Erica Marat, an associate professor at the National Defense University in Washington, D.C., and an expert on law enforcement in former Soviet countries, the GKNB has always been politicized and usually loyal to the government. In past years, it has also arrested people on trumped up or falsified charges, and even killed regime opponents.

In recent years, it has also taken aim at civil society, she said.

“They basically want to silence [Temirov], but they are also sending a larger signal to the entire society: ‘Don’t participate in all these processes you call democratic,’” Marat told OCCRP.

Even low-profile activists are sometimes targeted. An activist from southern Kyrgyzstan, who requested anonymity for fear of attracting further attention from the security agency, said that the GKNB tried to hack her Twitter account, likely in retaliation for her criticism of the Kyrgyz government’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic.

They also tried to trace her down using her phone number, but her SIM card was registered to another person, she told OCCRP. She found out about it after that person reached out to her through a colleague and let her know GKNB agents had come visiting.

“It’s really interesting that they were not chasing the real influencers with large numbers of followers. They were chasing activists like us,” she said.

But when the security agencies truly set their sights on a person, they don’t usually stop at social media. And often their approach is similar to the one used against Bolot Temirov.

In May 2020, the GKNB called Kamil Ruziev, a veteran human rights activist from the northeastern city of Karakol, in for a meeting. According to him, the official reason was to discuss four petitions Ruziev had filed against the GKNB for failing to investigate a police officer who had previously threatened him.

In a conversation with OCCRP, Ruziev said that when he arrived at the local GKNB branch, the officers held him in a room, threatened and tortured him, and tried to force him to testify that he had falsified a doctor’s note as part of a previous case. Ruziev says he did not give into their demands.

Ruziev only managed to get out of custody two days later, after declaring a hunger strike and experiencing a spike in his blood pressure. Almost immediately, he received word that he had been charged with falsifying documents back in March and also was being charged with defrauding the people he assisted as a rights defender.

According to Ruziev, prosecutors later dropped the fraud charges after his accusers came forward and said that GKNB officers had forced them to make false accusations against him. But the document falsification charge remains to this day.

Psychiatry on a Corpse

Temirov isn’t the only critic of the authorities to face politically motivated charges this year. Two months after the raid on Temirov LIVE, video blogger Batmakan Jolboldueva was arrested on a charge — “causing death by negligence” — that is stunning in its absurdity. She faces two other charges, including falsifying documents.

Jolboldueva had built up a sizable following in her native Batken Region, the most remote part of Kyrgyzstan. In early February, she came into conflict with Alikhan Uraimov, chief of staff of the presidential representative to the region. He was caught on camera hitting her. Uraimov claimed Jolboldueva had provoked him, and she was ultimately charged with “hooliganism.”

Then, in March, Jolboldueva recorded a local journalist, Arzygul Galymbetova, meeting with the regional governor and two investors in a cafe late at night and published the video online. Galymbetova pressed charges against Jolboldueva for violating her privacy and released a video accusing her and another blogger of placing a curse on her. She died the following night.

Medical examiners concluded that Galymbetova died from an asthma attack. But then law enforcement did something strange: They ordered a psychiatric evaluation of her corpse. When they found no signs that the journalist suffered from psychiatric conditions, investigators used testimony from her sister and witnesses to charge Jolboldueva with causing Galymbetova’s death through negligence.

Soon after her arrest, in a separate case Jolboldueva was charged with falsifying documents for allegedly faking the signature of a co-founder when registering her civic organization People’s Control “Batma-Bat.” She remains in custody.

Ruziev has no illusions about what is happening in Temirov’s case. He told OCCRP that planting drugs on a person or accusing them of inciting ethnic hatred are the easiest possible ways for law enforcement to launch criminal cases against journalists and activists.

The GKNB may have been preparing to use the latter approach against Temirov as well. In its analysis of Temirov LIVE’s videos, a GKNB colonel concluded: “We do not exclude the possibility that the above mentioned publications contain signs and actions aimed at public calls for a violent seizure of power and the fomentation of ethnic, national, or interregional hatred.”